DURING MY THIRTY-ONE YEARS at the Kennedy Space Center I spent six of them working at what was then called Unmanned Launch Operations, or ULO; first for a two-year stint, and later on a four.

I did no real work on the first two American manned space programs, Mercury and Gemini, but did work the Apollo Program from very early to the end, and the Space Shuttle Program from before the first launch until I retired at the end of 1996. That second for-year period at ULO occurred during the interregnum between the end of the Apollo Program and the first launch of the Shuttle.

The US is again in such a waiting period, with no American manned launches planned before 2016, or quite possibly 2017. And these will be limited to ferrying crew members to and from the International Space Station. The more ambitious program in work, developing a vehicle and spacecraft capable of sending humans to the Moon or Mars, is years to a decade away from its first manned flight—and that assumes the program doesn’t eventually get canceled as too expensive.

Unmanned launches, though, remain quite busy. The local newspaper, Florida Today, serves both the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral areas, hence provides more extensive coverage of unmanned launches than probably any other paper. I get to keep up, at a surface level, with what’s happening with my old outfit—now morphed into primarily commercial operations, with NASA buying launches like any other entity when it’s time to launch a scientific, weather, or other government-funded spacecraft. The Air Force also uses these contractors for military launches, including the GPS satellites that provide an extremely valuable service most of us now take for granted.

I had been at KSC for only about six months, working for a support contractor as a tech writer in a general writers pool, when I was abruptly offered a transfer—including a nice promotion—to a position then called “Project Writer” for the Atlas-Centaur Program. This included manning a console during launches, the responsibility there being to listen to the countdown progress on several channels, take notes on major events and problems, and update the electronic countdown status board at the head of the launch control center.

Between launches I prepared the NASA pre-launch technical documents (working with several engineering departments who provided the basic data, of course), and the after-launch mission report documents.

I received that promotion, after a rather short period of work as a general writer, over the heads of several other writers with more seniority and experience. My particular background made my managers think I would probably be successful in what was one of the most difficult jobs they had to support. They were, of course, right. And that first two years made some important differences in my life.

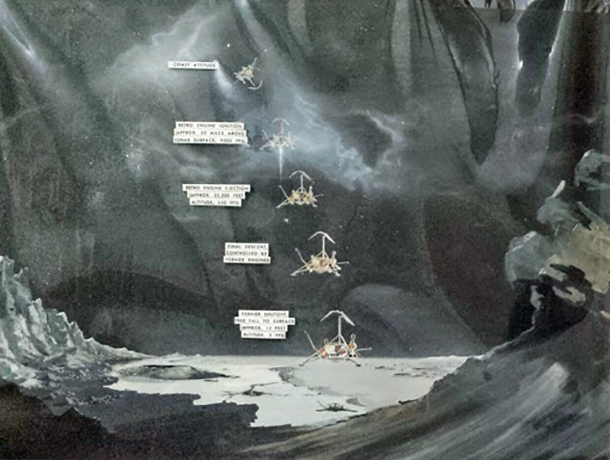

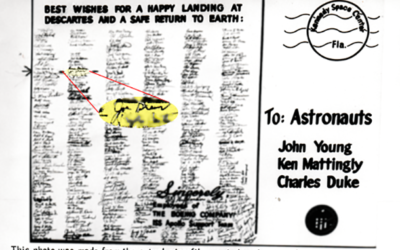

The second time I manned a console for an Atlas-Centaur launch was May 30, 1966. The payload was Surveyor 1, which became the first successful soft landing by a US spacecraft on another planetary body, the Moon (the Russians had gotten there four months earlier, but with a much less capable spacecraft). Unlike the robotic landers of today, Surveyors couldn’t move. But Surveyor 1 did return 11,000 photographs of the lunar surface, providing a great deal of the data the Apollo Program needed to prepare for that historic landing by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin in 1969.

I took advantage of the experience to do a science article (well illustrated with photos, including the status board in the launch control center), and it became my first sale to John Campbell at Analog. I followed it with several more science articles, then began selling him science fiction as well.

The Analog article, which circulated widely at KSC, brought me to the attention of some high-level NASA and contractor managers. That launched me into a secondary line of work—ghost-writing science papers for these executives. Those, and other more mundane work, eventually led to a position in NASA itself. I retired as Deputy Chief of the Education Office.

Though I spent my last eighteen years at KSC working in other areas, I’ve always been thankful for those six at ULO. They opened up career paths nor previously available to me, and led to what I enjoy now—a retirement in which I’m still writing fiction (no more science articles; too demanding) and a happy life.

Image credit: Courtesy of Joseph Green

0 Comments