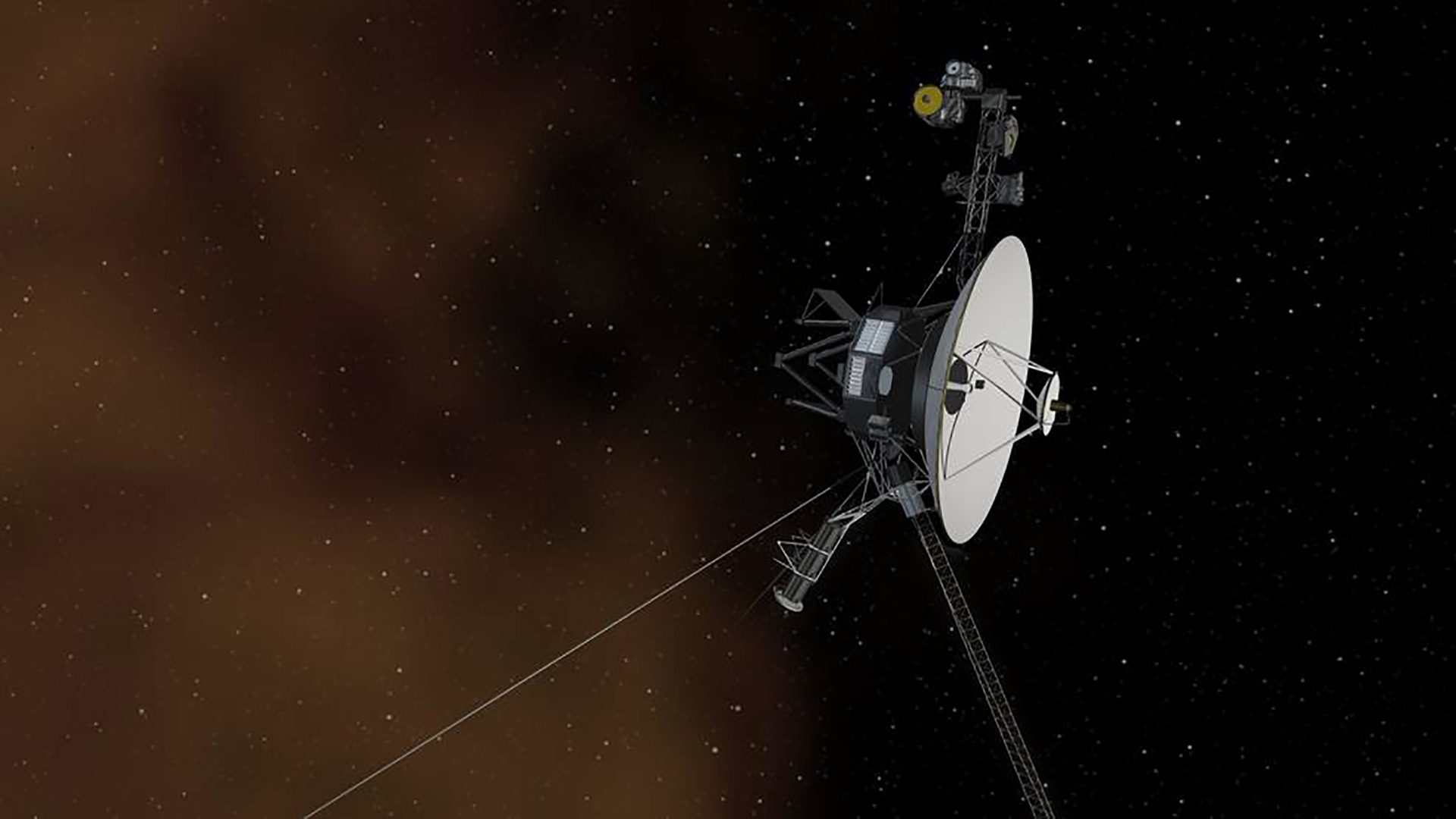

EARLIER THIS YEAR the local paper, Florida TODAY—highly space-oriented, since its territory includes the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and NASA’s Kennedy Space Center—carried a front page story that brought back vivid memories. The article said that space scientists, working from accumulated and analyzed data, had finally agreed that the Voyager I spacecraft entered interstellar space on August 25, 2012. Up until then the exact time had been a matter of dispute. The spacecraft is still operating, and expected to have enough power to keep sending back reports from at least one sensor until about 2025.

In 1977 I manned a console as a member of the Atlas/Centaur launch team. I also prepared the A/C technical documents, including the “NASA Fact Sheet(s)” distributed in advance of each launch. These were a compilation and distillation of the most important basic data on both spacecraft and launch vehicle. They were carefully written for the layman, explaining the mission in terms understandable to most high school juniors. These fact sheets became very popular with non-technical Kennedy Space Center personnel, the general public, and in particular the news media (the last for obvious reasons—a lot of their work done for them).

Although I wasn’t a member of their teams, the Delta and Titan/Centaur managers tasked me with preparing fact sheets for their missions as well. The larger and much more powerful Titan/Centaur had been chosen as the launch vehicle for the Voyagers because of the weight of the highly sophisticated (for their time) robot explorers, and the unusually high velocity required to reach Jupiter in only 18 months.

After a close-up exploration of Jupiter and several of its moons, Voyager I went on to Saturn for another flyby, then headed into interstellar space. The last was basically frosting on the cake, as was the famous photo Voyager I took on February 14, 1990, looking back at the Solar System (showing Earth as a “pale blue dot”). The two most important mission objectives had been successfully accomplished. Few expected this hardy explorer to still be functioning and reporting back when its escape velocity of 17 kilometers per second (in relation to the Sun) took it into interstellar space. But it’s there, and with another decade (hopefully) of life expectancy.

The accomplishments of the Voyagers have been reported and widely discussed in the media. For me, they trigger reflection and thoughts on perspectives. Mine is that of a teenager reading science fiction in the 1940s, never dreaming that mankind would land on the Moon in my lifetime (by 2050, maybe?). And sending a robot into interstellar space was in the far, far future, something my great-grandchildren might try. And yet I not only lived to see both, I actually played a small role in these two great scientific adventures. Those of you growing up at a time when you rather expected to see men walking on the Moon, or robots reporting back from interstellar space, may have an entirely different perspective.

Sometimes the glamor and excitement of manned space flight overshadows the accomplishment of the Voyagers, Pioneers, and other doughty robotic explorers. But in many ways, unmanned spacecraft have contributed more to our knowledge of the solar system and galaxy than the manned programs. We’ve now had robot explorers do close-up, highly instrumented flybys of all eight planets, and one is on its way to the disenfranchised Pluto/Charon system. These accomplishments are worthy of more respect than they have received from the world at large. Just ask any astronomer or space scientist which has contributed the most to human knowledge.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

0 Comments